Calligraphy

Discover Japanese Calligraphy: A First-Time Traveler’s Guide

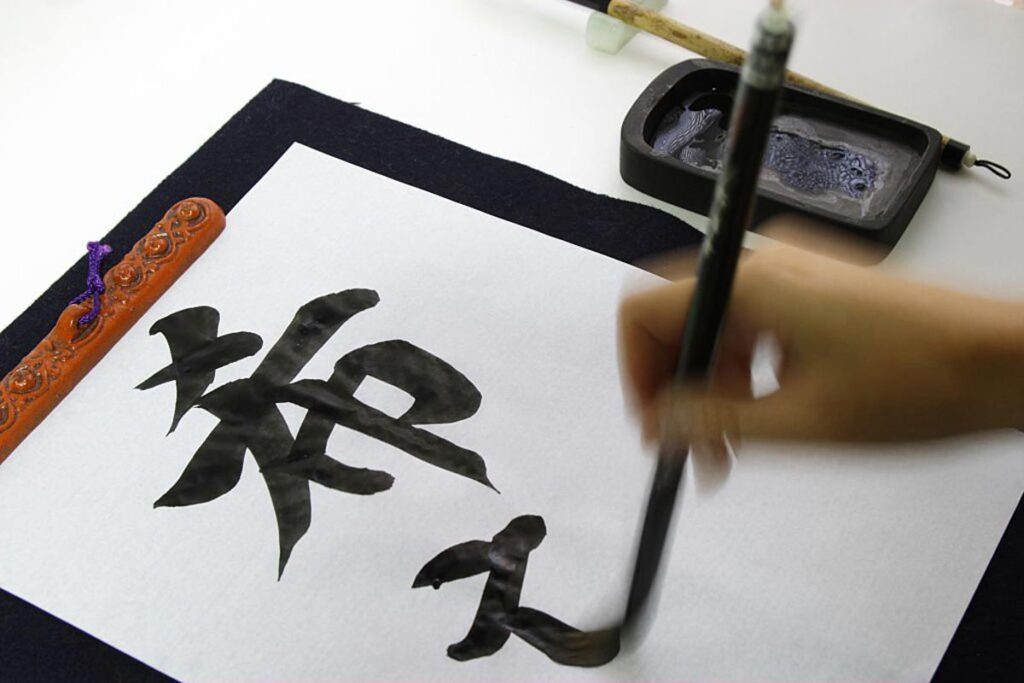

For many visitors, Japanese calligraphy is one of the most elegant and mysterious aspects of the culture. Graceful black ink on white paper, a single bold stroke, and a quiet room where time seems to slow down—this is the world of shodō, the “way of writing.” If you are visiting Japan for the first time, experiencing calligraphy is a memorable way to connect with the country’s history, aesthetics, and spirit of mindfulness.

What Is Japanese Calligraphy (Shodō)?

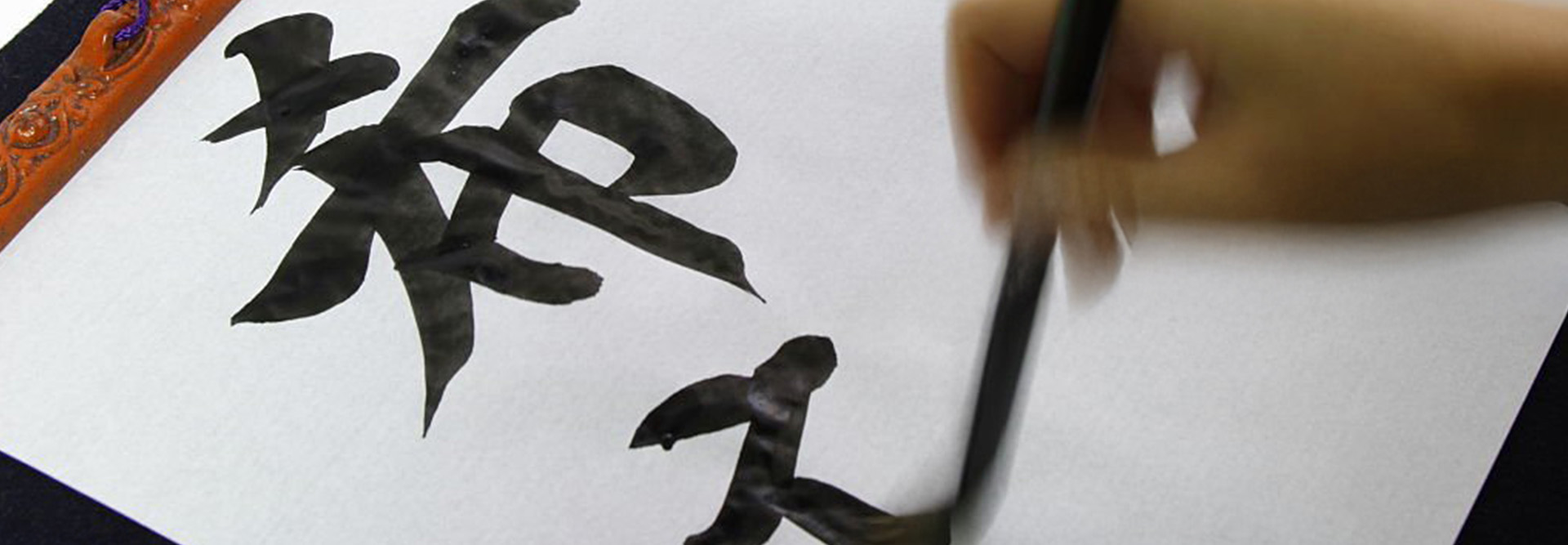

Japanese calligraphy, known as shodō (書道), literally means “the way of writing.” It is both an art form and a spiritual practice. Instead of focusing only on beautiful handwriting, shodō emphasizes balance, rhythm, and the state of mind of the calligrapher. Each character is written in a single, continuous flow, and once the brush moves, there is no erasing or correction.

Calligraphy in Japan uses Chinese characters (kanji) as well as the Japanese syllabaries hiragana and katakana. A simple word such as “heart” (kokoro, 心) or “dream” (yume, 夢) becomes a piece of visual poetry. The shape of each line, the thickness of the ink, and even the empty white space on the paper all carry meaning.

A Brief History of Japanese Calligraphy

Calligraphy arrived in Japan along with Buddhism and classical Chinese culture over 1,000 years ago. Early Japanese monks and scholars studied Chinese models intensely, mastering the brush styles of influential Chinese calligraphers. Over time, Japanese artists developed their own distinct styles, blending Chinese characters with flowing, cursive kana unique to Japan.

During the Heian period (794–1185), calligraphy became a hallmark of refinement among the aristocracy. Poems and love letters were written in graceful, sweeping script; the way you wrote was as important as what you wrote. Later, Zen Buddhism profoundly influenced shodō. Zen monks used calligraphy as a form of meditation, creating bold, spontaneous works that tried to capture a single instant of insight.

Today, calligraphy remains woven into everyday life in Japan. Children learn it at school, New Year’s celebrations often include calligraphy traditions, and many homes display a hanging scroll with a favorite character or seasonal phrase in the tokonoma (alcove).

Why Calligraphy Matters in Japanese Culture

To understand Japanese calligraphy is to understand the Japanese sense of beauty. The art form reveals several key cultural values:

Imperfection and the Beauty of the Moment

Shodō is closely related to the idea of wabi-sabi, the appreciation of imperfection and transience. No two characters are ever exactly alike, and a slightly uneven line or splash of ink can be part of its charm. Once the brush has touched the paper, you can only move forward—much like in life.

Mindfulness and Concentration

Practicing calligraphy requires deep focus. In traditional teaching, students are encouraged to calm their breathing, straighten their posture, and clear their thoughts before the first stroke. The resulting work is believed to reflect one’s inner state, so shodō is often described as “writing your heart” onto the paper.

Respect for Tools and Tradition

Every tool in calligraphy is treated with respect. The inkstone and brush are often cherished for years, and there is a quiet ritual in preparing ink and laying out the paper. This sense of care and precision reflects broader Japanese attitudes toward craft and tradition, from tea ceremony to ikebana (flower arranging).

The Essential Tools of Japanese Calligraphy

When you join a calligraphy workshop in Japan, you will likely encounter the classic “Four Treasures of the Study.” Understanding these tools adds depth to the experience.

The Brush (Fude)

The fude is the heart of calligraphy. Brushes come in various sizes, from thin and delicate to thick and powerful. They are traditionally made from animal hair, such as goat, horse, or weasel, which holds ink well and allows for both fine and bold strokes. The way you hold and move the brush determines the character’s personality.

The Ink (Sumi)

Traditional ink, or sumi, is made from soot and natural glue, formed into solid sticks. Instead of using ready-made liquid ink, calligraphers often grind the ink stick slowly against an inkstone with water. This process takes a few minutes and serves as a meditative preparation, helping you concentrate before you write.

The Inkstone (Suzuri)

The suzuri is a flat stone with a slight depression where water collects and the ink is mixed. A well-crafted inkstone can be used for decades, passed down from teacher to student. Its surface affects how the ink spreads and how rich the black becomes.

The Paper (Washi)

Washi, traditional Japanese paper, is made from plant fibers such as mulberry. It is both strong and delicate, absorbing ink beautifully while preserving subtle variations in tone. In workshops, you may use simpler practice paper, but you might also have the chance to write a final piece on higher-quality washi to take home.

Experiencing Calligraphy as a Traveler

You do not need any background in art or Japanese language to enjoy calligraphy. Many studios and cultural centers across Japan welcome beginners, including children. A typical experience combines cultural explanation, hands-on practice, and a finished piece as a souvenir.

What a Typical Calligraphy Lesson Looks Like

Most beginner-friendly lessons or workshops follow a similar structure:

- Introduction: Your instructor explains the basics of shodō, shows some sample works, and demonstrates how to hold the brush.

- Practice Strokes: You start with simple lines and basic shapes, learning how pressure, speed, and angle change the look of the ink.

- Writing Characters: You practice a few basic characters, often with meanings like “peace” (和), “love” (愛), or your own name rendered in kanji or katakana.

- Final Work: You choose a favorite character or word to write carefully on a piece of nicer paper, sometimes with a red name seal stamped on it.

- Souvenir: Your finished piece is usually mounted in a simple frame or folded so you can carry it home.

Many instructors are used to working with international visitors, so explanations are often available in simple English or with visual guidance that makes the process easy to follow.

Where to Try Calligraphy in Japan

Shodō experiences are available in most major cities, often in convenient locations for travelers.

Tokyo

In Tokyo, look for calligraphy studios and cultural centers in areas popular with visitors, such as Asakusa, Ueno, Shinjuku, and Shibuya. Some offer short, one-hour workshops ideal for busy itineraries, while others provide longer courses for those staying a few days. Larger museums and community centers sometimes host seasonal calligraphy events, especially around New Year’s.

Kyoto

Kyoto, with its many temples and traditional townhouses, is a particularly atmospheric place to try shodō. Some temples and cultural houses in districts like Higashiyama or Arashiyama offer calligraphy as part of wider cultural packages that might include tea ceremony or kimono dressing. Practicing calligraphy while overlooking a garden of moss and stone adds a special sense of calm.

Other Regions

Osaka, Kanazawa, Nara, and Hiroshima also have calligraphy workshops aimed at visitors. In smaller towns, you may find community-run cultural centers or local guides who can arrange a private session with a calligraphy teacher. Tourist information offices are often happy to point you to nearby options.

Seasonal and Temple Calligraphy Experiences

Certain times of year and special settings make calligraphy even more meaningful.

New Year’s Kakizome

At the beginning of January, many Japanese people take part in kakizome, the “first writing of the year.” They choose a word or phrase that expresses their hopes for the year ahead—such as “health,” “challenge,” or “gratitude”—and write it in bold strokes on fresh paper. Some cultural centers invite visitors to join this tradition, making it a memorable way to start the year if you are in Japan in early January.

Temple and Shrine Calligraphy

When visiting temples and shrines, you may see beautifully written characters on hanging scrolls, wooden plaques, and large boards. These are often created by resident monks or invited calligraphers. While casual visitors usually cannot write on sacred items themselves, some places offer calligraphy experiences in a separate hall, linking the practice to Zen meditation or Buddhist teachings.

Practical Tips for First-Time Calligraphy Students

To make the most of your calligraphy experience in Japan, keep these simple tips in mind.

Booking and Language

Popular studios in big cities often allow online reservations in English. Booking ahead is recommended, especially in peak travel seasons like spring and autumn. Check whether the lesson is suitable for beginners and whether explanations are available in English or with translation.

What to Wear

Ink can stain, so avoid wearing your favorite white shirt. Choose comfortable clothing and roll up your sleeves. Some studios provide simple aprons or smocks. You will usually sit at a low Japanese-style table or a standard desk, so wear something easy to move in.

Basic Etiquette

Calligraphy spaces are generally quiet and respectful. It is polite to:

- Arrive on time or a little early.

- Listen carefully to the instructor’s demonstration.

- Handle the brush and paper gently.

- Ask before taking photos, especially of the teacher’s work.

Do not worry about making mistakes; teachers expect beginners to be nervous at first. The goal is not perfection but presence.

Choosing a Character to Write

Many visitors like to write a character that holds personal meaning. Common choices include:

- 和 (wa) – peace, harmony

- 夢 (yume) – dream

- 心 (kokoro) – heart, spirit

- 愛 (ai) – love

- 旅 (tabi) – journey

Your teacher can suggest characters that are visually striking yet manageable for beginners.

Bringing Calligraphy Home

After your workshop, you will likely take home at least one finished work. Ask the instructor how long the ink needs to dry before you pack it, and consider storing it flat between cardboard or in a sturdy folder. Many travelers frame their calligraphy later as a reminder of their time in Japan.

Beyond your own work, you can find calligraphy-inspired souvenirs such as:

- Hanging scrolls with seasonal phrases or Zen sayings

- Postcards and art prints featuring famous characters

- Small ink sets or brushes for continued practice at home

If you buy original works from a calligrapher, ask for information about the artist and the meaning of the characters. This can add a personal story to your souvenir.

Why You Should Try Calligraphy in Japan

In a fast-paced trip filled with trains, crowds, and camera clicks, a calligraphy session offers stillness. For an hour or two, your whole attention narrows to the feel of the brush and the sound of ink moving across paper. You learn not only a traditional art, but also something about Japanese ways of seeing the world—valuing quiet concentration, subtle beauty, and the expression of the heart through simple tools.

Whether you join a formal class in Tokyo, a temple workshop in Kyoto, or a small community lesson in a countryside town, Japanese calligraphy is an accessible and rewarding experience for first-time visitors. You do not need to speak the language or be skilled at art. You only need a little curiosity and the willingness to let your hand—and your mind—follow the brush.

As you plan your journey through Japan, consider making room in your itinerary for shodō. Long after your trip ends, the characters you wrote may continue to remind you of the calm, focus, and quiet beauty you discovered along the way.